The Hawaiian Islands have very few permanent natural lakes. In fact, there are only four lakes on the main Hawaiian Islands (there is one on Laysan Island, as well). All four sit in the bottom of volcanic cinder cones or craters, making them pretty small in area, but potentially very deep.

- Lake Wai’ele’ele is located in a high-altitude rainforest in the East Maui Mountains.

- Lake Kauhako, on Molokai’s Kalaupapa Peninsula, has the highest ratio of depth to surface area in the world (meaning it’s pretty small, but very deep).

- Lake Waiau is one of the highest lakes in the U.S. (possibly #3, though that’s apparently disputed), located at over 13,000 feet elevation on Mauna Kea.

- Green Lake, in the Puna district of Hawaii, is probably the easiest to get to, as you don’t need a helicopter, mule, or 4-wheel drive vehicle to get to it.

- Oahu used to have a fifth lake, Salt Lake, which is now the site of a residential area and golf course (though there might be a remnant body of water there).

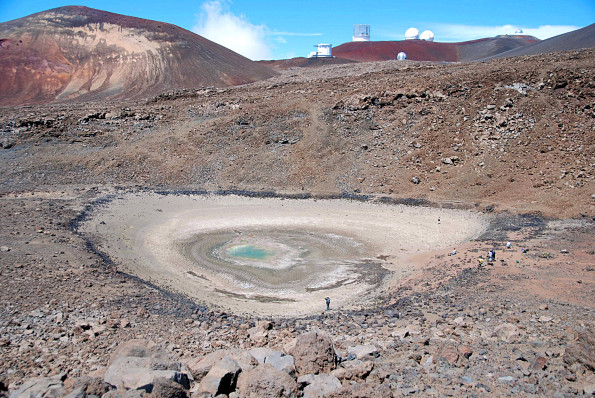

Lake Waiau has been in the news for the last few weeks for a very disturbing reason- it has been shrinking. A lot. As of late September, it was only at about 2% of its normal surface area!

Lake Waiau’s dramatic shrinking has been going on for at least a year. The reasons are not well understood, but are most likely linked to an ongoing drought in Hawaii, combined with rising temperatures. The lake is perched on what is normally really permeable volcanic cinders (think pumice stone). A layer of clay, permafrost, or some combination of the two (scientists aren’t sure which) rests under the lake bed, normally making the cinders stick together and holding the water in place.

In case you’re wondering, yes- permafrost. During the last Ice Age, there were glaciers on Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea, and there may still be frozen ground a bit under the surface of the top of Mauna Kea (Mauna Loa is too volcanically active). But if the lake is resting on permafrost, its days are numbered. High-altitude temperatures are increasing three times higher on Mauna Kea than the global average. Even if there’s not a melting layer of permafrost underneath, rising temperatures mean more evaporation, and when combined with little winter snowfall, clearly the lake is already in trouble.

As the only alpine lake in Hawaii, Lake Waiau was and is sacred to Native Hawaiians. From a scientific standpoint, its geology and ecology are unique. While its current problems likely stem from drought, its future is tied to our warming climate. Like many other unique and culturally significant locations worldwide, Lake Waiau’s fate seems to be one of drastic change.